Golf course architecture has traditionally been dominated by two things: the landscape and the routing. But UK-based golf course architect James Edwards is rethinking that. For him, great golf course design isn’t just about the walk from tee to green — it’s also about what happens before and after. The warm-up. The practice. The convenience of accessing all the facilities from the clubhouse. In short, the entire golfer’s journey.

A former elite player turned specialist architect, Edwards has spent the past 25 years designing short game academies, putting greens, driving ranges, and practice environments — not as afterthoughts, but as essential features in modern club masterplans.

His mantra? If the journey doesn’t start and end well, we let the modern golfer down.

Why ‘practice’ needs a seat at the table

“When I was a young player in Kent,” Edwards recalls, “I couldn’t find anywhere to practise my short game. I’d ask pros where they went, and they’d struggle to answer as well.”

That experience stayed with him. He realised that most UK clubs, even the most prestigious, had underdeveloped or awkwardly placed practice areas — if they had them at all. The root cause, he says, is legacy.

Older generations of architects just didn’t see practising as an important part of the game. In fact, golfers didn’t either. The changes seen in the professional game in the last 30 years have filtered through into club golf and the attitude towards practising has drastically changed.

Today, Edwards’ company, Edwards Design International (EDI), is working to reverse that legacy by integrating practice facilities as a key part of club life — both physically and philosophically.

The heartbeat of the golf club

At the centre of his vision is what he calls the Golden Hundred — a 100-yard radius around the clubhouse within which he aims to place everything that matters to the modern golfer: short game area, putting green, range, first tee and the 18th green.

“When you’ve got to get in a buggy and drive 400 yards to hit some practice balls, you’ve introduced inconvenience into the golfers experience” he explains. “That facility might look great, but it won’t be used the way it should.”

This thinking informed his recent work at The Wisley in Surrey — an example that perfectly illustrates the future-forward direction of modern design.

Practice as a statement of intent

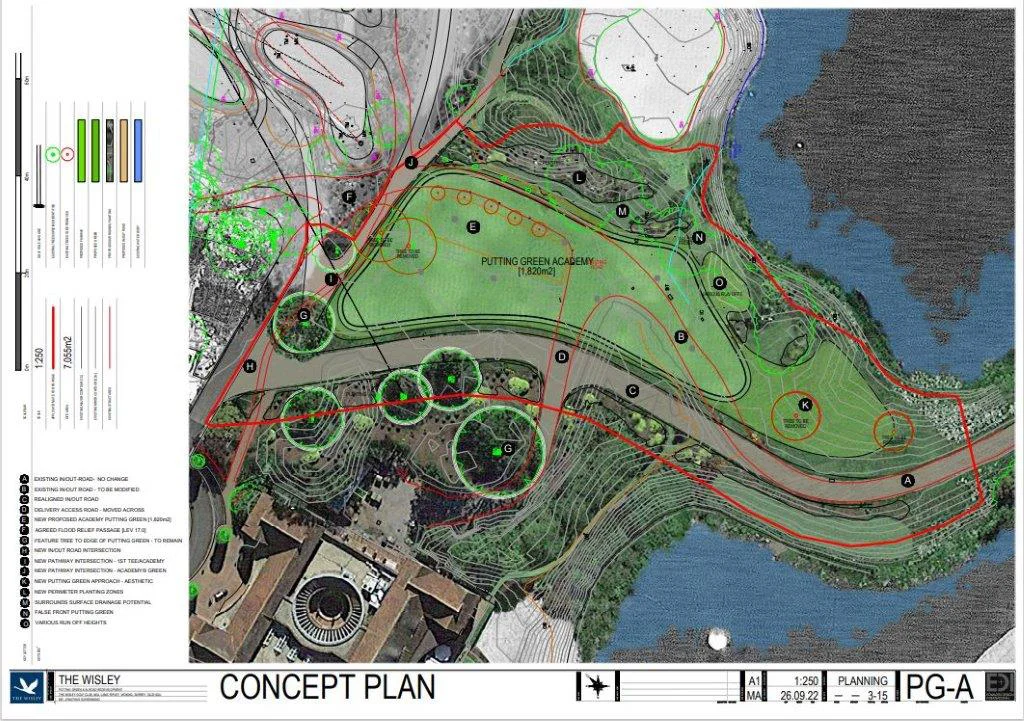

Widely regarded as the UK’s most progressive private member golf club, The Wisley recently made a statement in upgrading its already impressive practice facilities. James Edwards was brought in to design a new putting green within close proximity to the clubhouse — a space previously thought to be unavailable.

“The access road leads along a lake, flanked by beautiful landscaping to the clubhouse and car park,” Edwards explains. “But I saw potential. If we shifted that road and softened its curve, we could unlock 3,000 square metres of perfect practice space.”

The result is the most incredible putting green — a statement of intent to continuously improve the club’s facilities. Whether ambitious golfers or tour pros, the members at The Wisley couldn’t wait for the new green to open. In a matter of days from opening, it has become a treasured feature for both practice and warm-up.

Sometimes clubs must be bold

Reimagining a golf facility often requires bold decisions — and a willingness to disrupt the familiar. For many clubs, the clubhouse and its immediate surrounds are steeped in history and nostalgia. The first tee might be framed by ancient trees and even older stories. These spaces are sacred — and that’s exactly the problem.

“The 18th green might have emotional value,” Edwards admits. “It’s where someone’s dad holed a putt to win the club championship. I get it. We’re not here to dismiss that. But if moving that green back 50 yards creates a short game zone that every member will use every day, then we need to have that conversation.”

It’s not just about reclaiming land — it’s about reframing priorities. Golf, like any other sport, evolves. And for clubs to stay relevant, especially to younger generations of players and families, the layout around the clubhouse needs to support more than just nostalgia. It needs to function for the modern golfer.

Edwards believes that to create something better, you must be willing to rearrange the existing. That often means confronting long-held beliefs about what’s untouchable.

“It’s a mindset,” he says. “I’ve never taken a brief to create a practice area 400 yards away from the clubhouse. It might be a magnificent range, but it will be one that doesn’t fit into the golfer’s journey.”

Successful environments encourage engagement and guide people intuitively through the space. Edwards cites supermarkets, gyms, and even superstores like IKEA. “It’s all about effortless flow,” he says. “Golf clubs should be no different.”

That flow begins with proximity. When warm-up areas, short game facilities, and social spaces orbit naturally around the clubhouse, a club becomes more than just a place to play — it becomes a place to stay. A place where members linger, learn, and belong.

Still, resistance is common. The emotional attachment to a green or a first tee can be powerful — sometimes irrational. “People have hit their best-ever 7-iron into that green. I’ve lost the room on numerous occasions when suggesting moving such features of a course,” Edwards says. “But great clubs — really forward-thinking clubs — find ways to honour the past while embracing the future.”

“We don’t want to destroy the soul of the course,” Edwards adds. “We just want to be brave enough to ask: could it work better?”

A green built like a gym

One of Edwards’ most distinctive innovations lies in the deliberate and highly structured design of his short game practice areas. Unlike conventional putting and chipping greens, which are often flat and relatively featureless, Edwards approaches the space with clear intent. He divides the entire area into distinct, purpose-built zones, each replicating specific conditions a golfer might face not only on his home golf course, but on any course around the world. These zones include uphill lies, downhill lies, false fronts, tight lies, and bunkers with varied depths and angles. Each one is crafted to isolate and challenge a particular skill or shot type.

Edwards likens the experience to a gym workout. “You use specific machines and areas to train specific muscle groups. It’s organised, not random. That’s how people actually improve,” he explains.

This methodology ensures that players focus their attention, measure progress, and build confidence systematically, rather than working aimlessly.

Even the bunkers, often overlooked or seen as mere aesthetic additions in many practice facilities, are thoughtfully calibrated to maximise learning potential. One bunker might be designed with a gradual transition along its length to an increasingly higher lip, requiring greater skill to escape at the higher points.

“It’s not about how many bunkers you have,” Edwards stresses. “It’s about what those bunkers teach.” By embedding educational purpose into every contour, slope, and undulation, Edwards has transformed the short game area from a casual warm-up spot into a highly effective environment.

Designing for the next generation

For Edwards, designing practice facilities is about strategic investment in the future of golf itself. As the demographics of club membership evolve, with younger generations bringing new expectations, the traditional golf club model is being challenged. Today’s younger players and members are looking for more than just access to a tee time.

“Put a short game area, a putting course, a great driving range, and an amazing restaurant all within a hundred yards of the front door, and now you’ve got something special,” he says. It’s a holistic approach.

By designing with this mindset, Edwards believes clubs can attract and retain younger members, keeping the game thriving for years to come. The future of golf, he suggests, depends on how well clubs can evolve beyond tradition and craft spaces that lead golf into the future, spaces that excite the next generation of golfers and offer opportunities for them to learn and improve, without losing the history and traditions of the great game.